Fiction: “Spacey” by Melinda Smoot

Spacey

by Melinda Smoot

He wasn’t a bad teacher or anything, just spacey. My dad even hinted that he was spacey when he came home from back to school night. My dad, the math guy, said my geometry teacher, Mr. Alvarez, was spacey. Actually, I think my dad really said Mr. Alvarez reminded him of an aerospace guy, whatever that meant. I suppose that’s about as much of a mean comment my dad could muster up when it came to a teacher. Mean words certainly weren’t going to come out of my mom’s mouth unless the teacher was coming at me with a knife or something.

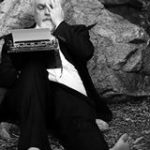

Mr. Alvarez definitely wasn’t going to come at anyone with anything, much less a knife. He was shorter than most of the students, and you could tell he had spent a large portion of his life hunched behind a computer because his head was poised on a neck that was cricked slightly forward. He was bald on top, but the hair he did have around the base of his head was thin curly and kept the back of his glasses warm. My friend Hillary said he looked like a seventy five year old version of Squints from the movie Sandlot. When he opened his mouth, he was nowhere near as cool as him.

“Good afternoon, mathematicians,” Mr. Alvarez had said the first day. His voice sounded like a vacuum that was set on the wrong setting.

“Mathematicians,” Bruno muttered from behind me. The brim of his baseball cap bopped the top of my ear, “he does know we’re only here because we have to be, right?”

While other teachers simply handed out syllabi and read from it verbatim to get everyone accustomed to their rules, Mr. Alvarez began the class with no syllabus and a dot to dot illustration of the ranks and files of “Seventy Six Trombones”. He then spent the remaining hour attempting to show us how to prove the maximum quantity of trombonists allowed on turn of the century streets would be only about five in rank, which made the files enormously long and what a parade that would be!

It didn’t take long for other students to start doing their own thing while Mr. Alvarez rambled. We hadn’t even thought about solving equations for three months, and suddenly the geometry teacher was ready for us to go straight into complex proofs. Bruno was playing his own dot to dot game between his right and left hand—where you make squares out of dot to dots. His right hand was winning.

Being raised by southern parents, my background was to smile and nod. Unless something was explicitly wrong, you just treated people with common decency as a citizen of the human race. Mr. Alvarez was a part of the human race, at least in some small fraction of his DNA, I hoped. Bless his heart.

We went home that night with homework of “prove your room is or isn’t a perfect square”, but we hadn’t even checked out geometry book, or any math book for that matter. I stayed up until eleven that night staring at my notebook paper that said Geometry, fifth period, Mr. Alvarez at the top before my dad told me I best get to bed—No good math happened after eleven. I simply wrote the sentence on my paper saying “My room isn’t a square because it’s passed eleven and my bed is a rectangle.”

The next day, my Geometry class had been cut in half. Hillary was gone. Bruno had enough space in front of his desk that he could stretch his legs out and nap while Mr. Alvarez talked. Mr. Alvarez did seem to notice the lack of attendance, but in his words, we were the ones who would be working for NASA someday, and all who missed were simply losing out. That hour was spent attempting to show us how isosceles triangles factored into a cue ball’s movement in Billiards. He didn’t even collect the homework, which all but infuriated me.

~ ~ ~

“Does he not realize I was up all night doing his homework?” I snapped at Bruno on the way home. I had crumpled the paper I had stared at the late hours of the night into a ball and tossed it towards a trashcan. It missed. I kicked the paper up towards the trash again, and when it missed a second time, I kicked the trashcan itself.

Bruno had more colorful choices of words for what he thought of Mr. Alvarez, ones that I can’t repeat for the sake of my soul. “I’m not going to class tomorrow,” he said as we stopped at the nearby 7-11.

“You’re ditching?” I asked while he grabbed some Big League chew and a Sprite.

“No, I’m going to get my mom to get me out of there,” he said. After handing the cashier a few dollars, he took his stuff, and we left. He shoved a finger full of Big League chew and blew a large bubble. It popped before he continued, “I’ve not learned anything there. Simple as that.”

For a small moment, I wished that I had Bruno’s parents, but I knew, eventually, it would have to get to that point if I complained to mine enough.

~ ~ ~

The following day, Bruno was gone and class attendance was a total of six. Mr. Alvarez’s eyes were dark. His face was gray. His voice was deep. He looked straight in my eyes and asked, “Why do you suppose the class has gotten so small?”

I bit my lip. I wanted to say because although it was clear he knew his geometry principles, it was also clear that he lacked a certain something when it came to teaching high school students. I never really got a chance to speak though, because one of the few remaining students spoke for me.

“Because we haven’t learned anything,” she said. Her fake eyelashes seemed to sassy clap together as she spoke.

Mr. Alvarez’s eyes narrowed. He grumbled that we should pick up our math books.

“We don’t have any,” I said.

“Then listen and listen good. That’s how us older and wiser ones did it,” he said. He uncapped his dry erase marker and drew a circle. This was going to be his moment, I knew it. He outlined the circle with his dry erase marker again.

“Say you have a round patch of land,” he began.

“You mean a cir—” I started, but Mr. Alvarez interrupted.

“No! We don’t know it’s a circle!” He pointed his Expo marker at me as though it were a ruler poised at the ready to slap me between the eyes.

“It looks like one based on your drawing,” another student said.

Mr. Alvarez stood and walked around the empty desks. He hid his dry erase marker behind his back and explained, “I know my drawing looks like a circle, but geometry is about proof with support of mathematic principles. We have to prove this is a circle. How would we go about doing that?” he asked.

The class was silent. It wasn’t because we didn’t want to participate, but because we had absolutely no idea how to go about proving this drawing was—indeed—an actual circle. We certainly didn’t have geometry books we could cross reference yet either.

Mr. Alvarez could tell we were struggling. He moved toward the white board and drew a line from one edge of the circle out to the top right corner. “Okay, let’s change things a little bit here, shall we?”

I rubbed my eyes and yawned. When my yawn was gone, I saw two lines drawn out to a point in the top right corner of the whiteboard, although the second line was from almost the opposite side of what might have been the circle, should we have the knowledge to prove it. “Say you and your family are prepping claim for your homestead out west. This circular plot looks nice and wonderful, doesn’t it?”

“Sure,” I said.

He drew two covered wagons at the point where the two lines crossed, “But your rival, Sparky Mcgee is eying that land from his camp also. You gotta get there before him.” Mr. Alvarez told a lovely story about how your rival was only a thousand miles away, and you had to make a trip of about fifteen hundred miles with a young child who was dying of dysentery and a broken wheel that needed repair. It was as if he were transporting us back to the good old days of playing Oregon Trail on the Apple 2E in kindergarten. His eyes seemed to light up while going on about how life was so complicated back then, and we had a much longer trek to make just based on the data alone. He was quoting theorems that we hadn’t learned yet, but soon would learn in his own words. It was easily the most animated moment I had ever seen come from a math teacher. For a moment, even I wanted to believe that this would be a moment when he showed just how wonderful math was.

Then there was a sudden pause, and his face dropped. Three other students were busy passing notes, but I could see a small sparkle in the corner of his eye. A small freshman student in the front row broke the inevitable silence.

“Mr. Alvarez,” she asked.

Mr. Alvarez held up an empty palm in reply, effectively silencing the student of any potential for criticism, though judging from the thickness of this freshman’s glasses, I’d be surprised if there was any kind of utterance similar to that.

“I’m very sorry, mathematicians,” Mr. Alvarez said. His voice was slightly higher than usual. He turned to the drawing on the whiteboard and wiped at his eye. Condensation was beginning to form on his glasses. He threw the Expo marker onto the tray by the eraser and said, “there is no such circle like this.”

The entire class was hushed. Even the students who were passing notes back and forth seemed to stop.

Mr. Alvarez picked up the eraser and lifted it toward the circle that he had proven wasn’t a circle after all. The eraser shook as he made contact with the whiteboard. It would have only taken a few seconds to wipe the whiteboard clean and have his mistake behind us, but he seemed to choose to keep the shape on there. Perhaps it was the fact that he had, at long last, received our undivided attention at the most inconvenient time—everyone knew he had messed up.

“We all make mistakes,” I said. I knew plenty of teachers who had written or done something wrong in front of students, but this shape seemed to completely unwind Mr. Alvarez to his very core. This circle, or not circle, had suddenly proven to him that he had chosen an incorrect path somewhere in his life—not that he had simply made a miscalculation in a moment of manic illustration.

Mr. Alvarez lowered the eraser into its cradle with his Expo marker. The shape—whatever it was—stared at all of us.

I sat there, torn. The geometry teacher who just seconds ago had excitedly belted off mathematical principles collapsed into the chair at his desk defeated. I wanted to give him a hug, but that was not the time or place to do that.

What I had seen before as a sparkle seemed to grow into a tear. It moved from his eye to the bottom rim of his glasses. Several other tears joined and pooled there until Mr. Alvarez lifted his glasses to rub his eyes. The tears then coasted down his cheek despite the fact that he tried to bite them back. The room stayed completely quiet until the bell rang and fifth period was finally over.

The six of us who remained left the room with Mr. Alvarez spewing tears onto his black loafers. I thought I heard him saying “What a waste” as we left.

~ ~ ~

By the following day, all the remaining students had all been reassigned to different geometry teachers. My new teacher, Mr. Moreno, reminded me of Fozzie Bear from The Muppets. He would clap his hands together and say “Come on guys” when we misbehaved, but he brought us back to the basics of geometry—where proofs meant “Prove triangle ABC and triangle DEF are similar”.

There was a small bit of mystery to what exactly happened to Mr. Alvarez. Bruno swore he probably drank himself to death, but I held out hope that despite him obviously not fitting into the high school environment, he was off somewhere in a covered wagon, listening to seventy six trombones marching down an extremely small street.

________________________

Melinda Smoot

Melinda Smoot lives in Cypress California, where she and her husband have an ongoing  war with the air conditioner temperature. In her spare time, she enjoys karate and chasing her cat and dog around the house. She holds a Bachelor of the Arts in Creative Writing, Fiction emphasis.

war with the air conditioner temperature. In her spare time, she enjoys karate and chasing her cat and dog around the house. She holds a Bachelor of the Arts in Creative Writing, Fiction emphasis.